Meth addiction can start quietly and then reshape daily life. This article explains the clear, clinical signs of methamphetamine use and addiction, what they look like in real time, and when to seek urgent help. It focuses on practical steps, safety, and proven evidence-based treatments so families and individuals can act with confidence.

Key Takeaways

- Call 911 for emergencies: chest pain, seizure, very high fever, severe headache, one‑sided weakness, violent agitation or confusion; suspected fentanyl mix needs naloxone and never use alone

- Early signs often cluster: dilated pupils, rapid speech & jaw clenching, little sleep, then a hard crash, sudden secrecy or missed work

- Long‑term use shows up in the body and mind, weight loss, “meth mouth,” sores or infections, mood swings, paranoia; psychosis can appear at any stage

- First steps that help: speak calmly, set clear limits, offer water and food during the crash, track sleep and spending; ask for screening (DAST‑10, WHO ASSIST) and evidence‑based care like Contingency Management, CBT, and Motivational Interviewing… sooner is better

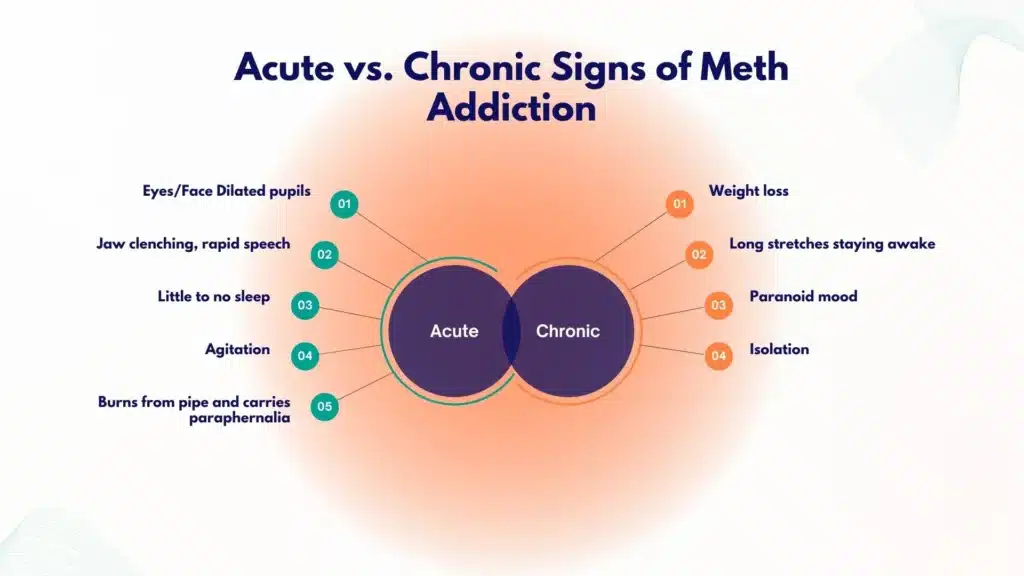

Core Signs of Meth Addiction: Acute vs Chronic Patterns

Acute Intoxication Pattern: What Shows Up Fast

In the hours after using methamphetamine, the body and behavior usually shift in obvious ways. Common short‑term signs include very large or dilated pupils, jaw clenching or teeth grinding, rapid pressured speech, and constant pacing or fidgeting.

People often appear hyperalert, scanning the room, easily startled, and unusually suspicious. Sweating can be heavy. Pulse and breathing may be fast. Many feel a surge of energy, talkativeness, and confidence that then tips into agitation.

Skin becomes dry; lips crack. Burns on the lips or fingertips can appear from hot glass pipes, torches, or heated foil. Some users switch to rectal application or injection to avoid smoke or burnt lips, leaving fewer obvious surface signs, yet increasing infection risk.

The Binge–Crash Cycle

Meth is often taken in runs that last for 1–3 days, sometimes longer. During the “binge,” sleep drops to an hour or two a night or not at all, food is skipped, and fluid intake is low.

After the binge, the “crash” brings extreme fatigue, long sleep, depressed mood, and irritability.

Some experience intense hunger, nightmares, and body aches. The crash can last 24–72 hours. When binges repeat, the cycle becomes predictable, several days up, then a hard down.

Chronic Use: What Accumulates Over Weeks to Months

Over time, the body shows wear. Weight falls as appetite is suppressed. Muscle mass thins; clothes hang looser. Hygiene often suffers.

“Meth mouth”, a combination of tooth decay, gum disease, and cracked or broken teeth, develops due to dry mouth, acidic drinks, grinding, poor brushing, and sometimes sugary sodas used for quick calories.

Skin picking becomes a pattern as people try to remove “bugs” they feel crawling (formication), leaving sores on arms, face, and scalp. These can get infected.

Long‑term use often flips the early energy into exhaustion between runs. Malnutrition is common. Socially, there is growing secrecy, lying about whereabouts, missed work or school, and relationships start to fray.

Money disappears quickly. New legal problems may appear, such as shoplifting, possession charges, and fights, tied to riskier decision‑making.

Environmental and Behavioral Clues at Home

Certain items signal active meth use. Look for glass pipes with bulb ends, small torches or lighters, scorched aluminum foil or hollowed pens, small baggies with white residue, and piles of spent batteries or chemical smells.

Windows covered in foil and sudden privacy, locked rooms, hiding phones, quick exits, are behavioral shifts to notice. Long drives at night and sudden new friends who appear at odd hours also fit.

Quick Comparison: Intoxication vs. Chronic Pattern

| Feature | Acute intoxication | Chronic/long‑term pattern |

|---|---|---|

| Eyes and face | Dilated pupils; jaw clenching; sweating; flushed face | Sunken eyes; dental decay; cracked lips; sores from picking |

| Speech and movement | Rapid, loud, pressured speech; pacing; fidgeting | Slowed, exhausted between runs; poor coordination during crashes |

| Sleep and appetite | Very little sleep; no appetite during runs | Binge-crash cycle; chronic insomnia; weight loss, malnutrition |

| Mood and behavior | Euphoria shifting to irritability, paranoia, agitation | Isolation, secrecy; missed work or school; legal and money troubles |

| Paraphernalia and injuries | Glass pipe, torches, burned foil; burns on lips or fingers | Same items plus infection signs; abscesses if injecting |

Intoxication often shows hypervigilance and agitation; long‑term use brings exhaustion, malnutrition, and social decline. Not everyone shows all signs. Age, dose, other substances (alcohol, benzodiazepines, opioids), and health conditions shift the picture.

Mental and Cognitive Changes

Anxiety, Irritability, and Mood Swings

Escalating anxiety is almost universal with repeated meth use. It may start as restlessness, grow into insomnia with racing thoughts, and then become irritability and anger.

Mood swings can be pronounced, energetic, and confident one day, withdrawn and negative the next. Sleep loss makes the mood more brittle. Loved ones often report walking on eggshells to avoid conflict.

Depression tends to surge during the crash and with prolonged abstinence early in recovery. Hopelessness can show up fast, especially if there is a history of mood disorder. This is a period of higher self‑harm risk.

Paranoia, Hallucinations, and Delusions

With heavier or repeated use, psychosis becomes more likely. Paranoia typically centers on being watched, followed, or plotted against. Auditory hallucinations (hearing voices, bangs, whispers) and visual hallucinations (shadows moving, flashing lights, bugs) may appear.

Delusions of persecution can lead to barricading doors, taping vents, or covering cameras. In some people, psychosis lingers for days or weeks after the last use, requiring medical care.

Violent outbursts are uncommon in the general population, but the risk spikes when paranoia and access to weapons coexist. Family and friends should prioritize safety planning before confrontation.

Attention, Memory, and Executive Function

Meth floods the brain with dopamine and norepinephrine, and over time, it disturbs circuits for attention, working memory, and planning.

People may misplace items, forget appointments, and have trouble focusing on tasks that used to be easy. Learning new information is harder.

These issues usually improve with abstinence, but not always fully, and they can make work or school difficult for months.

Co‑occurring ADHD or PTSD can complicate recognition and care. ADHD shares features, such as restlessness, impulsivity, and concentration problems.

A careful evaluation can separate baseline ADHD symptoms from stimulant effects. Guidance on this overlap is available here: ADHD and addiction.

Withdrawal, Depression, and Suicidality

Meth withdrawal is not typically medically dangerous in the way alcohol or benzodiazepine withdrawal can be, but it carries heavy psychological weight. For 1–2 weeks, fatigue, intense sleep, anhedonia (low pleasure), anxiety, and strong cravings are common.

Some people experience severe depression and thoughts of suicide. Any talk of self‑harm warrants immediate help; call or text 988 in the United States, or go to the nearest emergency department. If safety is unclear, do not leave the person alone.

Medical Risks and Red Flags Needing Urgent Help

Cardiovascular and Neurologic Emergencies

Meth stimulates the heart strongly. Chest pain, shortness of breath, and an irregular or very fast heartbeat may indicate a heart attack, arrhythmia, or aortic dissection.

Blood pressure surges can be extreme. In the brain, severe headache, confusion, difficulty speaking, facial droop, or one‑sided weakness may signal a stroke or brain bleed. These are time‑critical emergencies.

Hyperthermia, Dehydration, and Rhabdomyolysis

Body temperature can climb dangerously high, especially in hot rooms or during extended physical activity. Hot, dry skin, mental confusion, or collapse point to heatstroke.

Dehydration concentrates urine; muscles can break down (rhabdomyolysis), causing dark cola‑colored urine, muscle pain, weakness, and kidney strain. Early IV fluids in a hospital can be kidney‑saving.

Infections, Injection Risks, and Pregnancy

Skin sores from picking invite cellulitis. Injecting (“slamming”) raises the risk of abscesses, bloodstream infections, and endocarditis (heart valve infection). Shared needles or cookers increase transmission of HIV and hepatitis C.

For people who are pregnant, meth use heightens risks of high blood pressure, placental problems, preterm birth, and low birth weight.

Any fever, spreading redness around a wound, or chest pain with fever needs evaluation.

Fentanyl Contamination and Overdose Prevention

The stimulant supply is increasingly contaminated with fentanyl. This means overdose can happen even when someone believes they are only using meth. It is wise to:

- Carry naloxone and ensure close contacts know how to use it.

- Use fentanyl test strips where legal and available.

- Avoid using alone; if that is not possible, use a safety call service or have someone check in.

- Call 911 for slow or stopped breathing, bluish lips, or unresponsiveness.

CDC guidance describes how stimulant overdoses can look different from opioid overdoses; agitation, high temperature, and fast heart rate are prominent, but fentanyl mixing blurs the picture.

When in doubt, treat as an opioid overdose with naloxone and call for help.

Spot These Urgent Red Flags: Call 911

- Chest pain, severe shortness of breath, or fainting

- Severe headache with weakness, slurred speech, or confusion

- Hot, dry skin with agitation or collapse; seizures

- Dark urine with muscle pain and weakness

- High fever, a spreading skin infection, confusion, or unresponsiveness

Screening, Self‑Check and Next Steps

A Quick DSM‑5 Lens on Methamphetamine Use Disorder

Clinicians diagnose substance use disorder based on patterns, not just quantity. A brief self‑check can point to risk. Over the past 12 months:

- Loss of control and craving: using more or longer than intended; unsuccessful attempts to cut down; strong urges to use

- Harm and role failure: use causes problems at home, work, or school; continuing despite conflict or health issues; hazardous use (driving, overheating)

- Time and tolerance: spending a lot of time obtaining, using, and recovering; needing more for the same effect; relief of withdrawal symptoms relief

- Impact on life: giving up activities, isolation, secrecy, or legal and financial issues related to use

Two to three features suggest mild disorder, four to five moderate, six or more severe. A professional assessment refines this picture.

Brief screens can help structure concerns. Two commonly used tools are the DAST‑10 (Drug Abuse Screening Test) and WHO ASSIST. They are not diagnostic alone but provide a starting point to discuss with a clinician.

Step‑by‑Step: How to Document Patterns

Tracking patterns makes hidden issues visible and guides care. A simple approach:

- Choose a 7‑day window. Keep notes daily on sleep, mood, use, cravings, appetite, and spending.

- Record the time of last use and any triggers (stress, location, people).

- Note physical symptoms: heart rate if available, temperature, hydration, jaw clenching, sores, and dental pain.

- Capture consequences: missed classes or shifts, arguments, driving incidents, and police contact.

- Bring the log to a medical visit; it speeds up accurate care.

Consider including baseline medical data: blood pressure, weight, and any medications or supplements.

How to Plan a Calm, Safer Conversation

When raising concerns with someone who may be using meth, timing and tone matter.

- Pick a time after rest and food, not during intoxication or a crash.

- Start with care. Use “I” statements: “I’m worried because I noticed you have not slept and your heart seemed to race.”

- Share specific observations; avoid labels like “addict” or “meth head.”

- Offer choices, not demands: a medical checkup today or tomorrow; a phone call or a visit.

- Set clear safety boundaries: no driving while high; no using in the home; no weapons in the house.

- Plan for escalation. If threats, weapons, or severe paranoia appear, leave and call for help.

Write key points down beforehand. Keep it short; be ready to repeat later. Expect ambivalence.

Managing the Crash Safely at Home

If a person is not in medical danger, focus on the basics:

- Rest: dark, cool room; allow long sleep cycles.

- Hydration: water or oral rehydration solution; pause caffeine.

- Nutrition: simple, small meals with protein and complex carbs; consider a multivitamin and thiamine.

- Gentle movement: short walks to reduce soreness.

- Monitoring: watch the mood closely. If depression deepens, there is talk of self‑harm, or psychosis appears, seek urgent care.

Avoid alcohol or benzodiazepines to “come down”; they increase risks and complicate withdrawal.

Evidence‑Based Treatment: What Works

Treatment is more effective when it is systematic and individualized. Core elements:

- Contingency management (CM): small, frequent rewards for objective goals (negative drug tests, appointment attendance). CM has the strongest evidence for methamphetamine.

- Cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and Motivational Interviewing (MI): build coping skills, reduce triggers, and strengthen commitment to change.

- Medication approaches: There is no FDA‑approved medication for methamphetamine use disorder, but combined bupropion plus naltrexone has shown benefit in some adults in randomized trials. This is not a cure and should be prescribed and monitored by clinicians who can track blood pressure, mood, and interactions.

Medical care should also address sleep, nutrition, dental needs, and infections. For co‑occurring ADHD, PTSD, anxiety, or depression, integrated treatment improves outcomes.

Clinic‑based support, peer recovery services, and family education reduce relapse risk. Learn how clinics coordinate care here: role of substance abuse clinics.

Rolling Hills Recovery Center uses evidence‑based therapies and holistic supports, mind‑body practices, nutrition consults, and structured family involvement to help people stabilize and sustain change.

For high‑quality options in New Jersey, see the best addiction treatment in NJ.

Harm Reduction During any Stage of Change

A safety‑first plan reduces harm whether someone is cutting back or not ready to stop:

- Naloxone: carry it, teach friends how to use it, and replace before expiration.

- Safer supplies: sterile water, syringes, and cookers; never share equipment; rotate sites if injecting; clean skin before and after.

- Fentanyl testing: check supplies where legal; a negative strip is not a guarantee.

- Never use alone: use buddy systems or a safety call line; keep doors unlocked.

- Hydration and cooling: reduce overheating; take breaks; avoid crowded hot spaces.

- Driving and machinery: do not use while intoxicated; plan rides ahead.

Local syringe service programs and community groups can provide supplies, education, and testing for HIV and hepatitis C. Vaccination for hepatitis A and B is recommended for people at risk.

Coordinated Next Steps

A simple sequence moves from concern to action:

- Schedule a medical evaluation with a clinician familiar with stimulant use. Bring the daily log and a medication list.

- Request screening labs when appropriate: complete blood count, electrolytes, renal and liver function, CK (if muscle pain), pregnancy testing, HIV and hepatitis C testing with consent.

- Start evidence‑based behavioral care (CM + CBT/MI). Discuss whether bupropion plus naltrexone is appropriate and safe based on medical history.

- Build a crisis plan: who to call, when to go to urgent care, and how to keep naloxone accessible.

- Arrange follow‑up every 1–2 weeks initially. Add peer recovery support and family sessions.

If care has been fragmented or hard to access, specialized programs can take the lead in coordination and case management. Rolling Hills Recovery Center can provide comprehensive assessment, support transitions of care, and align treatment with the person’s goals and pace.

Practical Tools and Templates

Brief Readiness Checklist (For the Person Using)

- Am I willing to track sleep, food, and use for 7 days?

- Can I store naloxone where someone can find it quickly?

- What is one trigger I can change this week (place, person, time)?

- Who can I call if cravings spike?

Checking even one box is a start.

Conversation Script Starter (For Loved Ones)

“Because I care about you, I’m worried. I noticed you have not been sleeping, and your pupils were very large last night. I would like us to see a clinician today or tomorrow.

I can drive or arrange a ride. I’m not okay with driving after using or with unlocked weapons in the house. If now is not a good time, when later today can we talk for 10 minutes?”

Keep the script short. Write it out and practice once. If the response is hostile, pause and revisit when the person is rested.

Safety Plan Template (Post‑Visit)

- My warning signs: (e.g., no sleep >24 hours, chest pain, hearing voices)

- Immediate steps: hydrate, cool down, eat, contact support person

- Emergency thresholds: chest pain, severe headache, thoughts of self‑harm, no breathing, call 911

- Contacts: primary clinician, therapist, supportive family/friend, 988

- Location of naloxone and test strips

Returning to Work or School

After stabilization, structured routines help. Start with a partial schedule, ask for predictable shifts or classes, and plan for regular breaks.

Cognitive symptoms may persist, so using timers, written checklists, and a single notebook for tasks can make a large difference. Occupational therapy or academic support services add another layer of help.

Special Populations and Settings

Adolescents and Young Adults

Teens may present with rapid grade drops, new peer groups, and secretive phone use. Mood swings and insomnia are often misread as typical adolescent changes.

Early family‑based interventions and school coordination are key. Confidential adolescent‑friendly care can prevent a slide into legal problems and health harms.

Older Adults

Meth use in older adults is less recognized. Signs can be attributed wrongly to dementia or depression. Higher rates of heart disease and medication interactions increase risk. A lower threshold for medical evaluation is warranted.

Rural and Suburban Communities

Meth is not only an urban issue. In rural settings, distance to care and confidentiality worries can delay help. Telehealth options have expanded access. Coordination with primary care clinics and emergency departments improves safety during crises.

Co‑Use with Alcohol, Benzodiazepines, or Opioids

Some use alcohol or pills to “smooth out” meth effects. This combination raises overdose risk, masks early warning signs, and complicates withdrawal. A unified plan that addresses all substances is safer than tackling them one by one. Education about cross‑tolerance and drug interactions is part of every care plan.

Dental, Skin, and Sleep Care: Often Overlooked Basics

Dental Care

Dry mouth and acidic drinks accelerate decay. Simple steps: switch to water or sugar‑free options, chew xylitol gum, brush twice daily with fluoride toothpaste, and use a fluoride rinse at night. Arrange an early dental evaluation; extractions are not inevitable. Dental pain can trigger use; treating it reduces relapse risk.

Skin Care

For sores, gentle cleansing twice daily, petroleum jelly or antibiotic ointment on open areas, and clean dressings help. Avoid picking by covering lesions, trimming nails, and using fidget tools. Seek care for spreading redness, warmth, or fever.

Sleep Reset

After a crash, aim for a consistent lights‑out and wake time, a cool dark room, and a brief wind‑down routine. Limit screens for 30–60 minutes before bed. Short daytime naps (20–30 minutes) only. If insomnia persists beyond two weeks off meth, discuss short‑term sleep strategies with a clinician rather than self‑medicating.

Insurance, Privacy, and Access to Care

Most commercial plans and Medicaid cover assessment and outpatient therapy; contingency management pilots are expanding coverage. Ask programs about waitlists, telehealth options, and privacy practices.

Clinics must follow HIPAA; information is not shared without consent except in limited emergencies.

Coordinated programs can help with transportation, documentation for work or school, and letters needed for legal or employment purposes.

Resources

- NIDA overview on methamphetamine signs, risks, and neurobiology: NIDA Methamphetamine DrugFacts

- CDC guidance on stimulant overdose recognition and prevention: CDC Stimulant Overdose

- Consumer‑friendly clinical summary of meth effects and complications: MedlinePlus: Methamphetamine

- Peer‑reviewed evidence on bupropion plus naltrexone for methamphetamine use disorder: PubMed: ADAPT‑2 Trial

Conclusion

Meth addiction shows up as quick shifts in sleep, mood & energy, then physical changes and safety risks. Know the red flags, know when symptoms are an emergency, and use evidence-based care. Next steps: ensure safety, call 911 in crisis, have a calm talk, and book a professional assessment.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What Are the Earliest Signs of Meth Addiction?

Early signs of meth addiction often include sudden bursts of energy, little or no sleep, rapid or pressured speech, jaw clenching, and enlarged pupils.

Over days to weeks, other signs of meth addiction may appear: not eating with quick weight loss, picking at skin with new sores, “meth mouth” (tooth decay and gum problems), burns on lips or fingers, and a sharp drop in hygiene. Behavior changes, secrecy, mood swings, spending shifts, and missing work or school are common, too.

How Do Signs of Meth Addiction Differ From Anxiety, ADHD, or Simple Sleep Loss?

Timing and clustering help. Signs of meth addiction typically start abruptly and cluster together: rapid speech plus days awake, big appetite changes, noticeable weight loss, drug paraphernalia (glass pipe, burnt foil), and a “crash” after use.

ADHD or anxiety rarely causes severe jaw clenching, chemical burns, or repeated skin picking. Psychosis (paranoia, hearing or seeing things), chest pain, and overheating point more to stimulant misuse than to primary anxiety or insomnia.

What Emergency Red Flags in the Signs of Meth Addiction Require 911 Right Now?

Call 911 for chest pain, irregular heartbeat, seizure, very high fever or hot dry skin, one-sided weakness, severe headache, confusion, or violent agitation.

These signs of meth addiction can signal stroke, heart attack, or heat injury. If overdose is suspected, especially with possible fentanyl mixing, use naloxone if available and stay with the person.

Breathing problems, blue lips, or unresponsiveness are always emergencies & should be treated as such.

How Can a Family Member Respond When They Notice Signs of Meth Addiction?

Keep safety first. If there’s immediate danger, call emergency services. Otherwise, use a calm tone, short sentences, and clear boundaries.

Mention specific signs of meth addiction you have seen (for example, no sleep for 2–3 days, new skin sores, rapid spending) rather than labels.

Offer hydration, regular meals, and rest during the “crash.” Encourage a same-day medical check if there are chest symptoms, high fever, or hallucinations.

Plan for an evaluation and evidence-based care; bring trusted supports. Avoid arguing during intoxication; it rarely helps.

How Does Rolling Hills Recovery Center Address the Signs of Meth Addiction in Care?

Treatment begins with a thorough assessment that maps the signs of meth addiction to medical, psychological, and social needs. Treatment commonly includes Cognitive Behavioral Therapy and Motivational Interviewing, with careful medication monitoring.

When appropriate, off-label medication approaches may be considered, alongside nutrition support, sleep repair, and family engagement.

Aftercare planning focuses on relapse prevention, stable routines, and ongoing recovery supports.

Methamphetamine: https://nida.nih.gov/research-topics/methamphetamine

Stimulants: https://www.cdc.gov/overdose-prevention/about/stimulant-overdose.html

Methamphetamine: https://medlineplus.gov/druginfo/meds/a615002.html

ADAPT-2 Combination Naltrexone and Bupropion: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/36864016/

Author

-

Our editorial team includes licensed clinicians and board-certified addiction specialists. Every article is written and reviewed to be clear, accurate, and rooted in real treatment experience.

View all posts -

Dr. Williams has held senior leadership positions in the behavioral health field for over 30 years. He has worked with diverse populations in various private and public sectors.

View all posts