Alcohol Use Disorder is a medical condition with clear risk patterns, not a moral failing. This article explains the main causes and risk factors, how they interact, and what to watch for in New Jersey communities. Readers will learn practical prevention steps, screening options, and evidence-based care that support safer choices and lasting recovery.

Key Takeaways

- Alcohol Use Disorder is a medical condition, not a moral failing; risk builds from family history, early drinking, mental health, trauma, stress, and easy access in NJ communities.

- Early action helps: try brief screening like AUDIT‑C or SBIRT, set alcohol‑free days, pace drinks, eat first & hydrate, small steps add up.

- Risks vary by age and sex: women experience harm at lower intake; pregnancy risks are real; teens face binge patterns and mixing with vaping or cannabis; older adults have medication interactions and falls.

- Whole‑person care works best, treating anxiety, depression, pain, and sleep; add skills‑based therapy (CBT, MI), FDA‑approved medicines such as naltrexone or acamprosate; build family and community support… consistency matters.

Definition and Clinical Framing

Alcoholism is best understood today as Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD), a medical condition defined in the DSM‑5 by a pattern of impaired control, social impairment, risky use, and physiological criteria.

Severity ranges from mild (2–3 symptoms) to moderate (4–5) and severe (6 or more). AUD exists on a spectrum; it is not all or nothing.

Many people function outwardly while meeting criteria for AUD, which is why early signals should be taken seriously rather than minimized.

“Risk factors” increase the probability of developing AUD, but they are not destiny. Several risks combine and change over time. Genes, environments, stress, and culture interact. Protective factors can counterbalance them. Clear information and timely help make a difference.

A Quick New Jersey Lens

New Jersey’s landscape carries specific pressures and opportunities that shape drinking patterns:

- High availability in some towns with dense clusters of bars and liquor stores.

- Commuting stress, shift work, and industry demands can disrupt sleep and mental health.

- Shore tourism and seasonal events that normalize binge drinking for some groups, especially during the summer.

- Diverse communities with different cultural views on alcohol, offering both risks and supports.

Rolling Hills Recovery Center serves individuals across New Jersey with evidence‑based care, while respecting local realities such as commuting schedules, family responsibilities, and privacy needs. Information below is clinically grounded and stigma‑free.

Genetic and Family History

What is Inherited

Heritability estimates for AUD generally fall around 40–60%. That means genes contribute meaningfully, but environment still matters. AUD risk appears polygenic, driven by many genes each conferring small effects.

Variants in alcohol metabolism (for example, ADH1B and ALDH2) can alter how acetaldehyde accumulates and how alcohol feels, speeding or slowing reward and hangover responses. These variations interact with life events, stress, and social context.

A positive family history of AUD, especially in first‑degree relatives, roughly doubles the odds compared with the general population. That risk is not uniform; supportive environments, delayed drinking onset, and treatment engagement can cut it.

Family Environment

Children and adolescents learn by watching. Heavy parental drinking, arguments over alcohol, inconsistency in rules, and exposure to intoxication at family gatherings all raise risk.

On the other hand, parental warmth, clear and enforced rules about not drinking underage, and regular monitoring are protective. Predictable routines, meals, sleep, and homework also support resilience.

Practical Steps for Families

A simple approach can clarify risk without blame. Start by sketching a three‑generation family tree, noting any patterns of alcohol or drug problems, depression, anxiety, ADHD, bipolar disorder, suicide, trauma, and serious medical conditions (liver disease, pancreatitis).

List approximate ages of first drinking for each person if known. Patterns often emerge. Then, set two or three household rules that everyone understands, such as:

- No alcohol for anyone under 21.

- Adults do not drive after drinking.

- No alcohol kept in bedrooms.

Post the rules in a common space. If someone struggles, frame changes as health steps rather than punishment.

Mental Health, Trauma, and Stress

Depression, anxiety disorders, PTSD, bipolar disorder, and ADHD increase vulnerability to AUD, often through self‑medication. Alcohol can temporarily blunt distress, but it worsens mood, sleep, and attention long‑term.

The cycle deepens as tolerance rises and withdrawal symptoms (irritability, anxiety, poor sleep) pull a person back to drinking.

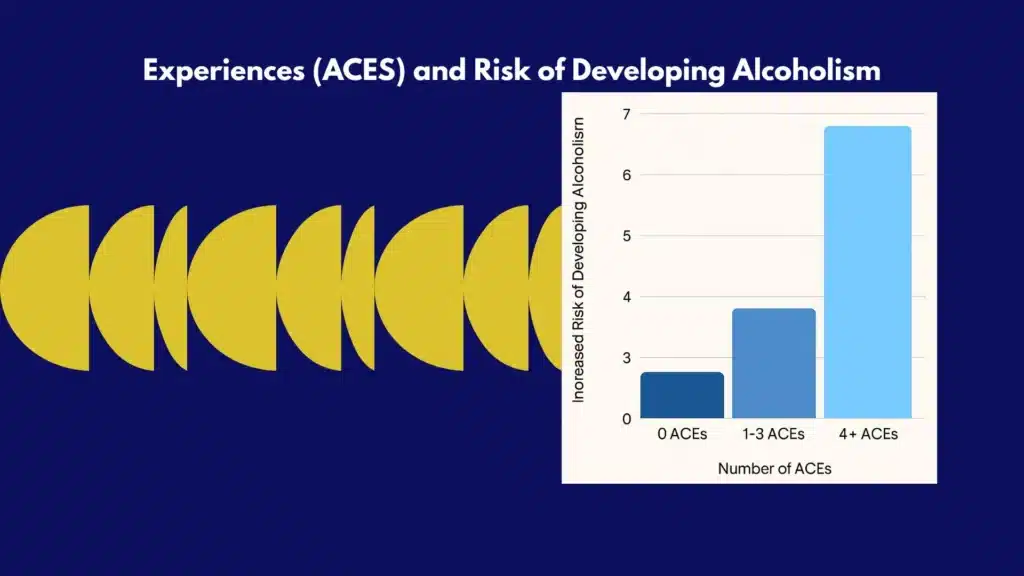

Adverse Childhood Experiences (ACEs), abuse, neglect, household substance use, parental separation, and violence predict a higher risk of early initiation, heavy drinking, and later AUD.

Chronic stress from housing instability, discrimination, unsafe neighborhoods, or high‑pressure work compounds the load on the nervous system.

Sleep problems and chronic pain are pivotal. Poor sleep amplifies cravings. Alcohol fragments sleep architecture, leading to more fatigue and more use the next day.

Pain conditions push some toward mixing alcohol with opioids, benzodiazepines, or sedating sleep medicines, which raises overdose risk. Grief, caregiving strain, and social isolation can also accelerate misuse, especially in older adults.

Integrated care works best. That means treatment plans that address mood, sleep, trauma, medications, pain, and alcohol together, not in silos.

At Rolling Hills Recovery Center, clinicians routinely coordinate with primary care, psychiatry, and family supports so that one part of care doesn’t undercut another.

Early Exposure, Adolescence, and College Culture

Starting to drink at a younger age is among the strongest predictors of later AUD. The adolescent brain is still wiring reward and impulse control; repeated binge patterns change those circuits.

In late teen and college years, social norms in sports teams, Greek life, or party houses can normalize heavy use. Media and influencer content often show alcohol without consequences.

Co‑use with vaping or cannabis can lower inhibitions and increase blackouts, driving risky mixing with alcohol.

Parents and guardians hold real leverage. Conversations started early and repeated calmly carry weight. New Jersey families often juggle tight schedules; short, frequent talks help more than one long lecture.

Tools like family media plans, alcohol‑free weekend activities, and well‑known community curfews reduce exposure to high‑risk settings.

On campus, involvement in clubs, intramurals, or service organizations is protective. Students who set a firm limit before events and alternate with water cut binge episodes significantly.

For those who appear to be “holding it together” with heavy drinking, consider reviewing high‑functioning signs, sometimes called functional alcoholism. For a deeper look at how this shows up in daily life, see what functional alcoholism can look like.

Social Determinants, Access, and Culture

Alcohol use does not sit only inside the person. The environment matters:

- Outlet density and pricing: More stores and bars in a small area, coupled with discounts or promotions, generally correlate with heavier drinking and harm. This is well documented across different cities and countries.

- Marketing: Targeted advertising influences youth initiation and adult brand loyalty. Sports sponsorships, seasonal promotions at the Shore, and social media placements matter.

- Peer networks: If friends socialize around drinking, revolve evenings around bars, or normalize drinking to cope, the person is more likely to mirror it.

- Occupations: Hospitality, nightlife, construction, transportation, healthcare, and first responder roles can mix irregular hours, high stress, and ready access. Shift work disrupts sleep and increases stimulant–alcohol cycles.

- Loneliness and limited recreation: When community options are scarce or expensive, alcohol often becomes the default social activity.

- Housing instability and financial stress: These add chronic stress that can fuel drinking as a coping tool, especially when mental healthcare access is limited.

Policy and community levers do help: zoning that reduces outlet clustering, price policies that discourage extreme discounting, and alcohol-free community events.

Investment in late‑night transit and safe rides reduces impaired driving. Local clubs, parks, recreation centers, and faith‑based groups offer social alternatives. Rolling Hills Recovery Center partners with families to build these supports into aftercare plans.

Veterans deserve specific mention. Combat exposure, chronic pain, sleep disruption, and moral injury can intersect with alcohol misuse. Integrated, trauma‑informed care with coordination through the VA or community resources is essential.

Sex and Age and Medical Comorbidity

Women, men, and older adults experience alcohol differently:

- Women generally have less body water and different enzyme activity, leading to higher blood alcohol levels per drink. They experience faster organ damage per unit of alcohol, liver disease, cardiomyopathy, and cognitive impacts. Breast cancer risk increases with even low levels of drinking.

- Pregnancy: There is no known safe amount of alcohol during pregnancy. Alcohol exposure can cause fetal alcohol spectrum disorders (FASD). Preconception and postpartum periods also carry unique risks due to sleep loss and mood changes.

- Older adults: Alcohol increases fall risk, worsens memory and balance, and interacts with common medicines, benzodiazepines, opioids, sedative‑hypnotics, antihistamines, and some antidepressants. Metabolism slows with age; the same amount produces higher blood levels.

Medical comorbidities shape risk: liver disease (fatty liver, hepatitis, cirrhosis), pancreatitis, hypertension, atrial fibrillation, stroke, certain cancers (mouth, throat, esophagus, liver, breast, colon), diabetes, and sleep apnea all worsen with alcohol.

For heart conditions, even modest drinking can provoke atrial fibrillation in susceptible individuals. Those with chronic pain face special danger if mixing alcohol with opioids or gabapentinoids.

Medications for AUD are safe and effective when used correctly. Naltrexone reduces reward; acamprosate helps stabilize glutamate systems; disulfiram produces an aversive reaction if alcohol is consumed.

Each requires careful medical screening, and disulfiram has important interaction risks (see below).

How to Check Personal Risk Now: Step by Step

- Track drinks for 7 days. Write down time, beverage type, and number of standard drinks (12 oz beer at 5%, 5 oz wine at 12%, 1.5 oz spirits at 40%). Use NIAAA’s drink size calculator at Rethinking Drinking.

- Take a quick screener. AUDIT‑C (3 questions) or full AUDIT (10 questions) are evidence‑based. A score of 3 or more for women and 4 or more for men on AUDIT‑C suggests risky drinking. Discuss results with a clinician.

- Compare to low‑risk limits. NIAAA’s commonly cited guidance: for men, no more than 4 drinks on any day and no more than 14 per week; for women, no more than 3 on any day and 7 per week. CDC frames moderation as 2 or fewer drinks per day for men and 1 or fewer for women, when not contraindicated. For pregnancy, driving, certain conditions, or some medicines, no amount is safe.

- Look for red flags. Blackouts, morning drinking, drinking to steady nerves, hiding bottles, missed work, fights, or driving after drinking indicate risk regardless of quantity.

- Set a 2‑week experiment. Choose alcohol‑free days; switch to low‑alcohol options; avoid drinking alone; make a plan for social situations (alternate with water; leave events earlier).

- Review medicines. Benzodiazepines, opioids, sleep aids, some diabetes meds, and warfarin can interact with alcohol. Bring the full list to a pharmacist or doctor.

- Decide next steps. If cutting back is hard or withdrawal symptoms appear (shaking, sweating, anxiety, nausea, insomnia), seek medical guidance. Rolling Hills Recovery Center can coordinate a safe, evidence‑based plan, including medications and counseling.

Template: 7‑day drinking diary

Date | Beverage | Standard drinks | Situation | Mood before | Mood after | Notes

Use it with a trusted clinician to spot patterns.

Useful Tools and Templates

- NIAAA’s Rethinking Drinking: drink size calculator, risk charts, and change planners.

- WHO AUDIT (Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test): validated screening.

- CDC Alcohol and Public Health: data and guidelines.

- APA’s resources on Alcohol Use Disorder: psychology‑based interventions and therapist locator.

Parents can adapt a simple “family alcohol plan.” One page should include: family rules; consequences; a text‑in curfew time; a ride‑home promise (“Call anytime, no questions asked”); and a monthly “check‑in” time. A brief conversation script helps:

“Because we care about your health and safety, we do not allow drinking before 21. If you find yourself in a situation with alcohol, text ‘home’ and we’ll pick you up. We won’t interrogate you that night; we will talk the next day.”

For community organizers and workplaces, a short policy toolkit can include: zero‑tolerance for intoxication on duty; clear paths to confidential help; alcohol‑free event options; safe‑ride codes; and training on recognizing impairment.

Comparative View: Risk Factor to Action

| Risk factor category | How it raises risk | What helps (practical levers) |

|---|---|---|

| Genetic and family history | Higher sensitivity to reward or withdrawal; modeled heavy use; conflict | Family rules; consistent monitoring; delay initiation; early counseling if problems arise |

| Mental health and trauma | Outlet density, pricing, marketing, isolation; shift work | Integrated care for mood, ADHD, PTSD; trauma‑informed therapy; sleep treatment |

| Early exposure and college culture | Binge patterns during brain development; peer norms | Parent–teen agreements; campus alcohol‑free events; screeners; limits before parties |

| Social determinants | Outlet density, pricing, marketing; isolation; shift work | Zoning and pricing policies; alcohol‑free recreation; peer support; sleep‑friendly schedules |

| Sex and age | Physiologic differences; pregnancy risk; polypharmacy in older adults | Lower limits; prenatal counseling; medication review; fall prevention |

| Medical comorbidity | Organ vulnerability: alcohol interactions | Disease‑specific counseling; medication alignment; regular lab and vitals monitoring |

Medication Cautions with Alcohol and AUD Treatment

- Disulfiram: Never combine with alcohol, including in sauces, some mouthwashes, or cough syrups, as it can cause flushing, blood pressure changes, nausea, and serious reactions. Interacts with metronidazole (risk of psychosis), warfarin (increased anticoagulant effect), and phenytoin (increased levels). A medical team should supervise.

- Naltrexone: Do not use with opioids; it can precipitate withdrawal and block pain treatment. People need to be opioid‑free for a safe period before starting. Monitor liver enzymes.

- Acamprosate: Renally cleared; dose adjusted for kidney function. Often best when the goal is abstinence.

- Benzodiazepines, opioids, sleep meds (zolpidem and others), antihistamines: Combining with alcohol increases sedation, respiratory depression, and injury risk.

- Antidepressants and antipsychotics: Some combinations raise sedation or metabolic risk. A prescriber should review.

If a person takes multiple medications, a single prescriber coordinating the full list helps. Pharmacists can perform interaction checks; bring every supplement bottle too.

Rolling Hills Recovery Center’s Approach in New Jersey

Rolling Hills Recovery Center provides individualized, evidence‑based treatment for AUD in a way that fits New Jersey’s lives. Care often begins with a medically supervised assessment and, when needed, a safe withdrawal plan. Core treatments include:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (CBT), Motivational Interviewing (MI), and trauma‑informed therapies that target triggers, thinking patterns, and stress recovery.

- FDA‑approved medications for AUD (naltrexone, acamprosate, disulfiram) are chosen to match goals, medical history, and daily commitments.

- Holistic supports, sleep and nutrition coaching, exercise planning, mindfulness, and family therapy, to restore balance across systems.

- Flexible scheduling for commuters and shift workers, and coordination with employers when confidentiality is critical.

Hidden, high‑functioning patterns are addressed with discretion and skill. For context on how alcohol problems can be missed in busy professionals, review this overview of functional alcoholism.

New Jersey‑specific resources, including data on local trends and support options, are summarized here: alcohol use in New Jersey. For veterans, integrated trauma‑informed pathways are available through our team and community partners; see the dedicated page on veterans programs in NJ.

Parents: Quick Steps to Lower Teen Risk

- Agree on three clear rules and post them (no underage drinking, call for a ride, no riding with a drunk driver). Enforce consistently.

- Know the plan: who, where, how they get home; require a text when plans change; keep alcohol locked.

- Model what you expect, no jokes that glamorize intoxication; avoid offering sips; plan alcohol‑free family activities.

When to Seek Urgent Help

If there are signs of severe withdrawal (confusion, seizures, hallucinations), chest pain, fainting, or serious injuries, call 911. If someone expresses hopelessness or suicidal thoughts, call or text 988 (Suicide & Crisis Lifeline) in the U.S. For non‑emergency but time‑sensitive help, shakes, persistent vomiting, or inability to sleep after cutting down, medical guidance is important; supervised withdrawal may be safer than trying at home.

How Clinicians Estimate and Track Risk

Clinicians combine screeners, laboratory data, and clinical interviews:

- Screeners: AUDIT/AUDIT‑C, TAPS, DAST (for polysubstance), PHQ‑9 (depression), GAD‑7 (anxiety), PCL‑5 (PTSD), ASRS (ADHD).

- Physical exam: signs of liver disease, neuropathy, cardiomyopathy, and cognitive changes.

- Labs: CBC (macrocytosis), CMP (liver enzymes, electrolytes), GGT, CDT (carbohydrate‑deficient transferrin), lipids, A1c if indicated, pregnancy test where relevant.

- Imaging: ultrasound or FibroScan for liver disease when appropriate.

- Collateral: with permission, insights from family or close contacts.

Treatment goals are tailored: abstinence for some, structured moderation for others, with safety always first. When moderation is attempted, clinicians set concrete metrics: max drinks per day and per week, no drinking on more than X days per week, and zero driving after any drinks.

Signals that Risk is Escalating

Watch for more time spent drinking or recovering, drinking earlier in the day, drifting away from non‑drinking friends, hiding containers, financial irregularities, more arguments, minor legal issues (public intoxication, disorderly conduct), and changes in sleep or appetite.

People sometimes call these “small fires.” Putting them out early, through counseling, medication, and routine changes, prevents bigger crises.

Those with co‑occurring opioid use or stimulant use face added risks. Alcohol may be used to come down from stimulants or to enhance opioid sedation.

If opioid misuse is present, dedicated care is needed alongside AUD treatment so both conditions improve together.

Rolling Hills Recovery Center provides integrated pathways and coordinates with prescribers to align medications, including MOUD for opioid use disorder when indicated.

Building a Protective Daily Routine

A steady routine is a powerful buffer:

- Sleep: set a consistent wake time; target 7–9 hours; avoid alcohol 3–4 hours before bed; reserve bed for sleep only.

- Meals: regular balanced meals stabilize blood sugar and reduce evening cravings.

- Movement: short daily exercise (even 15–20 minutes) lowers stress and improves mood.

- Connection: schedule at least two alcohol‑free socials each week, sports, coffee with a friend, volunteer hours, or a class.

- Coping kit: list five fast stress‑relievers (breathing exercise, music playlist, walk, call a supportive person, brief journaling). Keep it visible.

Write these into a weekly calendar. Small, repeatable changes often beat big, short‑lived swings.

Preparing for Social Events

Decide before arriving whether the plan is no alcohol or a strict limit. Bring or request alcohol‑free options. Practice two exit lines:

- “I’m the driver tonight.”

- “I’ve got an early morning; I’m skipping drinks.”

Have a rideshare app funded and visible on the phone’s home screen. If urges spike, step outside, text a support contact, and leave early if needed. These simple tactics reduce unplanned heavy drinking.

Documentation that Matters for Medical Visits

Arrive with a one‑page summary:

- Current drinks per day and per week; last drink date if stopping.

- Withdrawal symptoms experienced before.

- Medications and supplements, including over‑the‑counter and sleep aids.

- Medical history (liver, heart, pancreas, seizures, pregnancy).

- Mental health diagnoses and treatments.

- Goals: abstinence or moderation, privacy needs, and schedule constraints.

This helps clinicians match evidence‑based options quickly, from naltrexone to CBT to sleep interventions.

References and Further Reading

- National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism (NIAAA): https://www.niaaa.nih.gov/

Includes Rethinking Drinking tools, AUD screening, and treatment guidance. - CDC Alcohol and Public Health: https://www.cdc.gov/alcohol/

Data on health effects, guidelines, and community strategies. - World Health Organization Alcohol Fact Sheet: https://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/alcohol

Global risk data, policy levers, and health impacts. - American Psychiatric Association: Alcohol Use Disorder:

https://www.psychiatry.org/patients-families/alcohol-use-disorder

Clinical overview and links to care.

For New Jersey context and care pathways tailored to local needs, see: alcohol use in New Jersey.

Conclusion

Alcohol use risk is shaped by biology, stress, early exposure, and the environment. Key takeaways: risks stack; quick screening catches problems early; integrated care supports recovery. If risks are adding up, don’t wait, talk with a clinician & consider a brief screening today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What Are the Main Risk Factors for Alcoholism?

Risk factors for alcoholism include family history and genetics, early first drink, heavy or binge drinking patterns, mental health conditions (like depression, anxiety, PTSD, ADHD), trauma, and high-stress environments.

Easy access to alcohol, social norms that push drinking, and certain jobs (hospitality, night shifts) raise risk too.

Medical issues, chronic pain, and sleep problems can add to the pressure. Medications that interact with alcohol, benzodiazepines, opioids, and sleep aids make harm more likely. Risks add up; the more boxes checked, the higher the odds.

How Do Risk Factors for Alcoholism Show Up Differently in Women, Teens, and Older Adults?

Risk factors for alcoholism can look different across life stages. Women face faster organ damage at lower drinking levels and are more affected by trauma; pregnancy adds unique risks.

Teens who start early, binge on weekends, or mix alcohol with vaping or cannabis are at higher risk; the brain is still developing.

Older adults may drink less but have more medication interactions & balance issues, so harm rises quickly. Each group needs tailored screening and support.

Can Risk Factors for Alcoholism Be Lowered, and What Simple Steps Help Right Now?

Yes. Risk factors for alcoholism can be lowered with small, steady changes: track drinks; set alcohol-free days; avoid triggers like drinking games; and eat and hydrate before events.

Use a brief screener, such as the AUDIT-C (3 questions), and share results with a clinician; ask about SBIRT, a quick, office-based intervention. Treat anxiety, insomnia, pain, and PTSD with evidence-based care so alcohol isn’t used to cope.

Build support, family, peer recovery, faith, or community groups; move more, sleep regular hours. If in New Jersey, discuss safe driving plans around shore weekends & festivals and choose venues with alcohol-free options.

What Early Signs Suggest Risk Factors for Alcoholism Are Becoming Alcohol Use Disorder?

Risk factors for alcoholism may tip into Alcohol Use Disorder when warning signs appear: needing more to feel effects, drinking more or longer than planned, craving, skipping duties at work or home, risky situations (driving, fights), and cutting back on activities.

Blackouts, morning “eye-openers,” or withdrawal symptoms (shakes, sweats, anxiety) are serious flags. Conflict with family, repeated “I’ll quit tomorrow,” or failed cut-down attempts also point to trouble. A quick AUDIT-C or full DSM-5 checklist with a clinician can clarify next steps.

Author

-

Our editorial team includes licensed clinicians and board-certified addiction specialists. Every article is written and reviewed to be clear, accurate, and rooted in real treatment experience.

View all posts -

Dr. Williams has held senior leadership positions in the behavioral health field for over 30 years. He has worked with diverse populations in various private and public sectors.

View all posts