Alcohol Use Disorder affects health, families, and work. From a medical addiction specialist’s perspective, this article explains how clinicians identify AUD, gauge withdrawal risk, and choose safe detox & evidence-based medications, paired with therapy and ongoing support. It outlines practical steps, tools, and safeguards to improve outcomes while honoring dignity and safety.

Key Takeaways

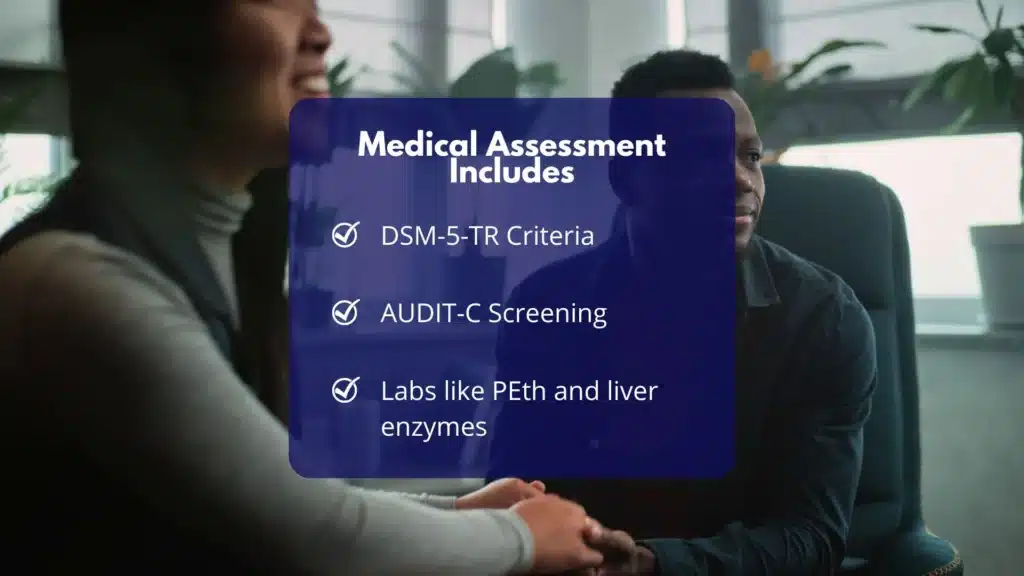

- Start with a clear medical assessment: DSM-5-TR criteria, brief screens like AUDIT-C, and labs (PEth, liver enzymes). Document goals, withdrawal risk, pregnancy status, and other health issues, then set a practical plan.

- Withdrawal care must be safe. Use CIWA-Ar and vitals to choose inpatient or outpatient. Give thiamine before glucose, manage fluids and electrolytes, and use benzodiazepines when indicated; adjust for liver disease.

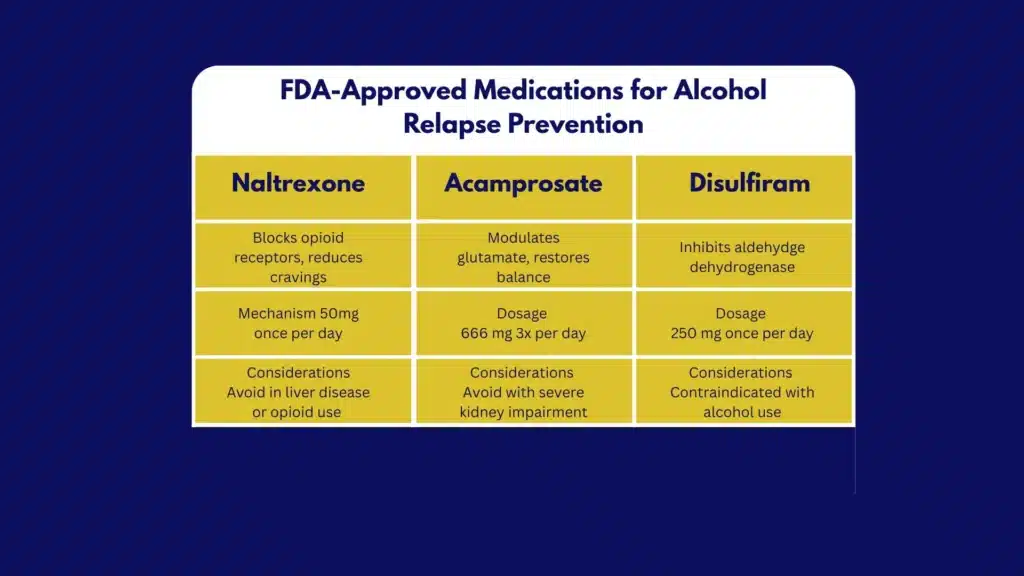

- Medications help prevent relapse: naltrexone lowers heavy drinking; acamprosate supports abstinence (good with liver concerns); disulfiram only with close supervision. Consider gabapentin or topiramate when first-line options don’t fit; check interactions and labs.

- Recovery works best when meds & therapy move together, CBT, motivational work, contingency strategies, plus sleep, nutrition, family support, and steady follow-up. Plan for lapses, vaccinate for HAV/HBV, and protect safety; small steps, measured often.

Assessment and Diagnosis of Alcohol Use Disorder (AUD)

DSM-5-TR Criteria and Severity Specifiers

AUD is diagnosed when at least 2 of 11 criteria occur within a 12‑month period. Severity:

- Mild: 2–3 criteria

- Moderate: 4–5 criteria

- Severe: 6 or more criteria

The 11 criteria include loss of control (larger amounts, unsuccessful cutbacks), time spent obtaining or recovering, craving, failure to fulfill major roles, social or interpersonal problems, activities given up, hazardous use, continued use despite harm, tolerance, and withdrawal. For a medical record, list each criterion met with examples. Use simple language with patients, while keeping documentation precise.

When the patient is actively intoxicated or in withdrawal, defer parts of the diagnostic interview until vital signs stabilize. NIAAA and WHO emphasize shared decision-making: clarify the patient’s goals (e.g., reduce heavy-drinking days vs. abstinence), then match interventions to those goals.

Quick Screening and Labs

A fast, validated screen is the AUDIT‑C (3 questions; score range 0–12). Cutoffs often used:

- Women and adults 65+: 3 or higher suggests risk

- Men under 65: 4 or higher suggests risk

Confirm with a full AUDIT when time allows or if scores are borderline. Document the baseline number of drinks per week, the number of heavy drinking days, and the largest number of drinks on any day.

Initial labs and objective measures:

- Liver panel (AST, ALT, bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase), albumin, INR

- CBC (macrocytosis/MCV elevation), electrolytes, glucose, magnesium, phosphate, renal function

- GGT and CDT, when available, aid in detecting chronic heavy use.

- PEth (phosphatidylethanol) in blood for objective detection of significant alcohol intake over the past ~2–4 weeks; useful for monitoring change

- Pregnancy test, where applicable

- Viral hepatitis (A/B/C) and HIV screening per risk and immunization history

- Consider thyroid, vitamin D, and B12 if symptoms suggest deficiencies

Document physical findings: tremor, diaphoresis, tachycardia, hypertension, ataxia, peripheral neuropathy, hepatomegaly, jaundice, or signs of Wernicke’s encephalopathy (confusion, ophthalmoplegia, ataxia). Link screening and labs to a plan: results should inform detox setting, medication choices, and medical monitoring.

Helpful tools and references: NIAAA Clinician’s resources (screening and brief intervention), WHO alcohol technical materials, and SAMHSA implementation aids.

Safety Triage for Withdrawal Risk

Any patient reducing or stopping heavy alcohol use needs a quick withdrawal risk check. Ask about:

- History of severe withdrawal, seizures, or delirium tremens (DTs)

- Last drink timing; typical daily quantity; morning “eye-openers”

- Concurrent benzodiazepine or barbiturate use

- Medical comorbidities (e.g., COPD, CHF), traumatic brain injury, or epilepsy

- Current vitals (tachycardia, hypertension, fever), agitation, or confusion

- Housing stability and the ability to attend daily visits if outpatient

- Pregnancy

Use the CIWA‑Ar to quantify symptom severity (0–67). CIWA‑Ar <8: mild; 8–15: moderate; ≥15: severe. Unstable vitals, hallucinosis, confusion, or a history of seizures/DTs push toward supervised detox.

Medical Comorbidities and Pregnancy Considerations

Common alcohol‑related comorbidities include alcoholic hepatitis, pancreatitis, gastritis, cardiomyopathy, hypertension, arrhythmias, sleep disorders, depression, anxiety, trauma, and neuropathy. Treat co‑occurring disorders in parallel because they influence relapse risk.

Pregnancy requires a higher standard of caution. Alcohol is teratogenic at any dose. Pregnant individuals with moderate to severe AUD or any withdrawal risk should be managed in a higher‑acuity setting with obstetric collaboration.

Medications for relapse prevention in pregnancy are generally avoided or used only when benefits clearly outweigh risks; focus on behavioral treatment, nutritional support, and careful withdrawal management.

Alcohol Withdrawal and Detox

Who Needs Inpatient vs Outpatient Care

Brief stratification using history, vitals, and CIWA‑Ar helps select the safest level of care:

Table: Typical indicators for detox setting | Indicator | Outpatient appropriate | Inpatient indicated | | — | — | — | | CIWA‑Ar | Mild (<8), stable | Moderate–severe (≥8 with risk), or rapid escalation | | History | No prior seizures/DTs | Prior seizures/DTs; failed outpatient | | Vitals/mental status | Stable vitals; oriented | Tachycardia, hypertension, fever, confusion, hallucinations | | Substances | Alcohol only | Polysedatives, benzodiazepine dependence | | Medical/psych | Minimal comorbidity | Significant comorbidity, suicidality, pregnancy | | Supports | Reliable support/housing | Poor supports or unsafe housing |

If in doubt, choose a higher level of care. Rolling Hills Recovery Center has partners that provide closely supervised detox with medical monitoring, which often shortens the dangerous portion of withdrawal and reduces complications. For local context, many people search for medical detox near me when symptoms like shaking, nausea, or rising blood pressure begin.

Medications for Withdrawal

Benzodiazepines remain first‑line. Two common strategies:

- Symptom‑triggered therapy: dose according to CIWA‑Ar assessment. For example, diazepam 10–20 mg every 1–2 hours or lorazepam 2–4 mg every 1–2 hours until CIWA‑Ar <8. This reduces total benzodiazepine exposure and duration of detox. Requires staff who can score CIWA‑Ar reliably.

- Fixed‑schedule therapy: chlordiazepoxide 50–100 mg every 6 hours on day 1, tapering over 3–5 days; or diazepam 10 mg every 6 hours day 1, then taper. Give rescue doses for breakthrough symptoms.

In significant liver disease, avoid long‑acting oxidatively metabolized benzodiazepines; use lorazepam or oxazepam.

Adjuncts:

- Gabapentin (e.g., 300 mg three times daily, titrate) can help mild–to–moderate withdrawal and reduce insomnia or anxiety; adjust for renal impairment.

- Carbamazepine can help with milder ambulatory withdrawal where benzodiazepines aren’t preferred; monitor for interactions.

- Clonidine or propranolol can dampen autonomic symptoms but are not seizure‑protective; use only as adjuncts.

- Antipsychotics (e.g., haloperidol) may be used for severe agitation/hallucinations with concurrent benzodiazepines; monitor QTc.

- Phenobarbital protocols are effective in experienced inpatient settings with continuous monitoring.

These approaches align with the ASAM Alcohol Withdrawal Guideline and are consistent with CDC alcohol resources.

Supportive Care: Thiamine, Fluids, Electrolytes, Hepatic Dosing

Supportive care saves lives and must be routine:

- Thiamine before glucose to prevent Wernicke’s: 100 mg IV or IM daily for 3–5 days; if Wernicke’s suspected, 200–500 mg IV every 8 hours for 2–3 days, then 100 mg daily orally. Add folate 1 mg daily.

- Fluids and electrolytes: replace magnesium, potassium, and phosphate as needed; correct hypoglycemia; avoid overhydration in cirrhosis or heart failure.

- Nutrition: high‑calorie, high‑protein diet as tolerated; multivitamin; treat nausea aggressively to enable intake.

- Liver disease: prefer lorazepam or oxazepam; titrate slower; monitor sedation closely.

- Sleep: target 6–8 hours nightly; minimize deliriogenic meds; consider melatonin when appropriate.

Ensure continuous reassessment. Even patients who start with mild symptoms can worsen quickly in the first 24–48 hours.

Practical Workflow

- Stabilize vital signs and begin thiamine.

- Decide setting using CIWA‑Ar, history, and support.

- Choose benzodiazepine strategy and adjuncts; set a taper.

- Start relapse‑prevention planning during detox; line up medication options and therapy follow‑up.

- Arrange warm handoff to ongoing care within 3–7 days. Rolling Hills coordinates medical, therapy, and family services so no step is missed.

Pharmacotherapies for Relapse Prevention

When to Start

Medication can start during or right after detox. Naltrexone is often initiated once opioids are cleared and acute withdrawal is controlled; acamprosate is started when abstinence is established (ideally within 7 days of last drink).

Disulfiram is started only after at least 12 hours of alcohol‑free time and when supervision is available. Off‑label agents are considered when first‑line options are contraindicated or not tolerated.

First‑Line Options

Naltrexone

- Oral: 50 mg once daily; some start at 25 mg daily for 3–5 days.

- Extended‑release (XR): 380 mg IM gluteal injection every 4 weeks.

- Best for: decreasing heavy drinking days, reducing craving, supporting harm reduction, or abstinence.

- Contraindications: current opioid use or anticipated opioid need; acute hepatitis or liver failure. Check LFTs at baseline and periodically. Counsel that opioids won’t work while on therapy and that overdose risk increases if opioids are used after naltrexone is stopped.

- Side effects: nausea, headache, fatigue; usually transient.

Acamprosate

- Dose: 666 mg three times daily; or 999 mg twice daily when adherence is better with BID dosing. Adjust for CrCl 30–50 mL/min to 333 mg TID; contraindicated if CrCl ≤30.

- Best for: maintaining abstinence, especially in liver disease, since it’s renally cleared.

- Side effects: diarrhea, anxiety, insomnia; minimal drug interactions.

Disulfiram

- Dose: 250 mg daily (range 125–500 mg).

- Best for: motivated patients choosing abstinence with reliable supervision (family, pharmacy, or clinic).

- Contraindications and cautions: severe cardiac disease, psychosis, pregnancy generally avoided, hepatic insufficiency; check baseline and follow‑up LFTs (e.g., at 1–2 months). Avoid with metronidazole. Patients must strictly avoid alcohol in beverages, mouthwashes, some sauces, and certain topical products to prevent a disulfiram‑ethanol reaction.

Off‑Label Options When First‑Line is Not Tolerated

Topiramate

- Titration: start 25 mg nightly; increase by 25–50 mg weekly to 100–300 mg/day in divided doses.

- Effects: reduces drinks per drinking day and craving.

- Cautions: cognitive slowing, paresthesias, weight loss, kidney stones; teratogenic risk; adjust for renal impairment.

Gabapentin

- Dosing: 300 mg three times daily; may titrate to 600 mg TID (max varies by patient).

- Effects: helps with craving, anxiety, and insomnia; useful for mild protracted withdrawal symptoms.

- Cautions: sedation, dizziness; adjust in renal impairment; assess misuse risk in select populations.

Medication Summary at a Glance

| Medication | Typical dose | Start timing | Best for | Key cautions/monitoring |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naltrexone oral | 50 mg daily | Abstinence maintenance: liver disease | Heavy drinking reduction | LFTs; no opioids; counsel on overdose risk |

| Naltrexone XR | 380 mg IM q4wk | Same as above | Adherence issues | Injection site reactions; same opioid cautions |

| Acamprosate | 666 mg TID | When abstinent | Reduce drinks/cravings | Renal dosing; GI side effects |

| Disulfiram | 250 mg daily | ≥12 h after last drink | Supervised abstinence | LFTs; no alcohol products; drug interactions |

| Topiramate | Up to 100–300 mg/day | Post‑detox | Cognitive effects, renal stones, and pregnancy risk | Cognitive effects, renal stones, pregnancy risk |

| Gabapentin | 900–1800 mg/day | During or post‑detox | Sleep/anxiety; craving | Sedation; renal dosing; misuse potential |

Clinical pearls and patient‑friendly handouts are available from NIAAA and SAMHSA pharmacotherapy materials. Shared decision‑making improves adherence; consider patient goals, organ function, side effect profiles, and contraception needs.

Monitoring and Managing Side Effects

- Baseline labs: LFTs for naltrexone/disulfiram; renal function for acamprosate, topiramate, gabapentin; pregnancy testing when relevant.

- Follow‑up labs: repeat LFTs 4–12 weeks after starting naltrexone or disulfiram; renal function if dosing high or symptoms suggest issues.

- Address side effects early: dose with food for naltrexone nausea; slow titration for topiramate; split dosing or loperamide for acamprosate‑related diarrhea; evening dosing for sedating meds.

- Drug‑drug interactions: review antibiotics (metronidazole with disulfiram), opioids (with naltrexone), and CNS depressants (gabapentin synergy).

Integrated Care and Psychosocial Supports

Evidence‑Based Therapies

Pharmacotherapy works best when combined with structured therapy:

- Cognitive Behavioral Therapy (skills for triggers, thoughts, and behaviors)

- Motivational Enhancement Therapy (aligns treatment with the patient’s values)

- Contingency Management (rewards for recovery behaviors)

- Community supports (SMART Recovery, 12‑step groups) if a patient is interested

Rolling Hills integrates medical and holistic modalities with therapy, family work, and peer recovery to strengthen outcomes. For a coordinated plan in New Jersey, see our approach to treatment for substance abuse.

Family, Sleep, Nutrition, and Harm Reduction

- Family involvement: invite partners or family to sessions with the patient’s consent; align boundaries, remove alcohol from the home, and set clear support plans. Consider Al‑Anon or parallel supports.

- Sleep: brief CBT‑I strategies, consistent schedule, limit caffeine after noon; avoid routine benzodiazepines or “Z‑drugs” for insomnia in AUD recovery.

- Nutrition: protein‑rich meals, complex carbs, multivitamin with thiamine (100 mg daily orally after parenteral course), folate; screen for eating disorders or severe malnutrition.

- Harm reduction: if a patient is not ready for abstinence, set limits and safety steps (no more than 1 drink/day for women or 2 for men when appropriate, never drink and drive, avoid mixing alcohol with sedatives). Some will transition from reduction to abstinence over time.

Co‑Occurring Conditions and Care Coordination

- Depression and anxiety frequently improve after 2–4 weeks of reduced drinking; reassess before changing long‑term medications. Treat persistent disorders per guidelines.

- Pain management: prioritize non‑opioid strategies; if opioids are required, avoid naltrexone and create a clear plan with informed consent.

- Liver disease: coordinate with hepatology; immunize against HAV and HBV; evaluate for cirrhosis and varices when indicated.

- Neurologic issues: evaluate peripheral neuropathy, cognitive complaints; consider neuropsychology if persistent.

- Pregnancy: coordinate with obstetrics; prefer inpatient detox if withdrawal risk exists; focus on behavioral treatments and nutrition.

Stigma reduction, confidentiality, and non‑punitive language are essential. Use patient‑reported outcomes such as the Brief Addiction Monitor (BAM) or PROMIS Alcohol Use.

Ongoing Monitoring, Relapse Prevention, and Continuity

Set Measurable Goals and Track Outcomes

Define success in concrete terms:

- Abstinence, or

- Fewer heavy drinking days (HDD: ≥5 drinks/day for most men or ≥4 for most women), fewer total drinks per week, and fewer alcohol‑related problems

Use simple tools:

- Timeline Followback (TLFB) to estimate daily drinking

- Brief Addiction Monitor monthly

- PEth to corroborate reduction or abstinence when clinically relevant

- AUDIT‑C or full AUDIT at baseline and periodically

Brief check‑ins every 1–4 weeks initially improve adherence. Telehealth reduces barriers. Text reminders, pill boxes, pharmacy blister packs, and long‑acting injections all support continuity.

Visit Schedule, Telehealth, and Adherence Supports

A practical cadence:

- Weeks 1–2 post‑detox: weekly visits or telehealth check‑ins; assess cravings, side effects, sleep, mood, safety

- Weeks 3–8: biweekly; review goals, counseling attendance, and labs if needed

- Months 3–6: monthly; consider stepping down frequency if stable

- After 6 months: every 1–3 months; maintain therapy and peer support

Medication adherence tips: set alarms, link dosing to daily routines, use XR naltrexone if adherence is a concern, involve a support person, and address cost/coverage directly.

Labs, Preventive Care, and Bone Health

- Labs: repeat LFTs for those on naltrexone or disulfiram; periodic renal checks for acamprosate, topiramate, gabapentin; monitor electrolytes in patients with ongoing GI losses or diuretic use.

- Vaccinations: hepatitis A and B; influenza annually; pneumococcal per guidelines in chronic liver disease; Tdap updates.

- Bone health: chronic heavy drinking raises fracture risk. Consider vitamin D and calcium; DEXA scan if malnutrition, hypogonadism, or steroid use.

Plan for Lapses and Safety Planning

Relapse is common and not a moral failure. Plan ahead:

- If drinking resumes: schedule a visit quickly; restart or adjust medication (e.g., resume naltrexone unless new contraindications); reinforce therapy; revisit triggers and coping skills.

- Crisis planning: provide the 988 Suicide & Crisis Lifeline; identify warning signs, supports, and local urgent care or ED contacts; if alcohol withdrawal red flags return (seizure, severe tremor, confusion), escalate care immediately.

- Driving and work: no driving with any alcohol on board; discuss employer policies for safety‑sensitive roles. Encourage early conversations with HR for leave or accommodation when needed.

- Legal risks: DUI education, family safety planning, and referral to legal aid when appropriate. Clinicians respect confidentiality except in cases of imminent risk; they emphasize a therapeutic, non‑punitive approach.

A simple relapse prevention plan template can be completed with the patient and revisited monthly:

- Early warning signs I notice

- People and places that trigger me

- My top three coping skills

- My medication plan if I slip

- Who I call in the first 24 hours

- Safe environments I can go to

- My next appointment date and time

Documentation, Coverage, and Community Resources

- Document medical necessity: DSM‑5‑TR criteria count, severity, functional impairment, medical/psychiatric comorbidities, prior treatment history, and risks that warrant the selected level of care. When relevant, map to ASAM Criteria dimensions for level‑of‑care determination.

- Prior authorizations: include objective measures (AUDIT‑C score, PEth or CDT, LFTs, CIWA‑Ar scores, number of HDDs), and failed/contraindicated therapies to support coverage for meds or higher levels of care.

- Community and educational resources:

- NIAAA Rethinking Drinking and Clinician’s Core Resources

- WHO alcohol brief intervention tools and technical packages

- SAMHSA helplines and clinician toolkits; FindTreatment.gov for national directories

- ASAM resources on withdrawal management and outpatient integration

For those seeking New Jersey‑specific information on prevalence, risks, and available supports, see our overview of alcoholism in New Jersey.

Putting it Together in Practice

A pragmatic, stepwise approach in medical settings:

- At the first visit, screen quickly (AUDIT‑C), quantify drinking, and order baseline labs (LFTs, CBC, electrolytes, PEth if monitoring will be needed). Check pregnancy tests where appropriate.

- Assess withdrawal risk (history, vitals, CIWA‑Ar). Choose outpatient or inpatient detox accordingly; give thiamine before any glucose and start the detox plan.

- During detox, engage in motivational interviewing; set an initial goal (abstinence or harm reduction) and discuss medication options that match medical comorbidities and patient preferences.

- Within 3–7 days, initiate pharmacotherapy (naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram) with clear counseling and a side‑effect plan. Arrange therapy (CBT, MET) and peer support.

- Follow up weekly early on; monitor side effects, adjust doses, and confirm safety. Track heavy drinking days, cravings, and sleep. Use PEth selectively to corroborate progress.

- Over 3–6 months, maintain therapy and medications; adjust based on patient‑reported outcomes. Address depression, anxiety, pain, and sleep as part of one integrated plan.

- Relapse management is built in: encourage rapid re‑engagement without guilt; update the plan, problem‑solve triggers, and keep momentum.

Conclusion

Recovery from alcohol use disorder is possible. It starts with careful assessment, safe withdrawal, then meds that fit you, plus therapy & steady follow-up. Key takeaways: screen early, manage withdrawal safely, and combine medications and counseling for better outcomes. Ready to act? Contact Rolling Hills Recovery Center today.

Frequently Asked Questions (FAQs)

What Does Medical Treatment for Alcoholism Include?

Treatment for alcoholism starts with a clear assessment of drinking patterns, health history, and signs & symptoms. It often includes safe withdrawal care (detox) when needed, using medications to prevent seizures & delirium, plus vitamins like thiamine before glucose.

After stabilization, evidence-based medications such as naltrexone, acamprosate, or disulfiram can reduce cravings or support abstinence. Care works best when combined with counseling, skills-based therapy, family support, sleep and nutrition planning, and regular follow-up.

The aim is fewer heavy-drinking days or sustained abstinence, better health, and steady function at home and work.

How is Safety Managed During Withdrawal in Medical Treatment for Alcoholism?

Safety comes first. A clinician checks past withdrawal problems, seizures, other substances, pregnancy, liver disease, and vital signs. Some individuals do well with outpatient care; others need supervised, inpatient monitoring.

Symptom scales (like CIWA-Ar) guide short-term use of benzodiazepines. Fluids, electrolytes, and thiamine are routine. The team watches for red flags, rising heart rate, confusion, worsening tremor, so treatment is adjusted quickly. After the acute phase, the plan shifts to relapse-prevention meds & therapy.

Which Medicines Are Used in Medical Treatment for Alcoholism, and Who Should Avoid Them?

Common options are:

• Naltrexone (pill or monthly injection) to curb reward from alcohol; not for those using opioids or with acute hepatitis.

• Acamprosate to support abstinence; preferred if significant liver disease, but adjust in kidney disease.

• Disulfiram to create an alcohol sensitivity; best with close supervision; avoid in pregnancy and severe heart or liver disease.

If first-line choices are not a fit, clinicians sometimes use off-label options like gabapentin or topiramate. Decisions weigh risks and benefits, current meds, and goals. Simple rule: never start without a clinician’s review of liver and kidney health.

How Long Does Medical Treatment for Alcoholism Take, and What Does Follow-Up Look Like?

Timelines vary. Detox lasts days; medication for relapse prevention usually continues for months, sometimes a year or longer. Follow-up visits are more frequent early on, then spaced out as things stabilize.

Teams track goals like abstinence, fewer heavy-drinking days, sleep, mood, and lab markers when indicated. Plans are adjusted; if a lapse occurs, care is not stopped, and treatment is fine-tuned.

Practical supports (reminder apps, family check-ins, telehealth) help with adherence & momentum.

Author

-

Our editorial team includes licensed clinicians and board-certified addiction specialists. Every article is written and reviewed to be clear, accurate, and rooted in real treatment experience.

View all posts -

Dr. Williams has held senior leadership positions in the behavioral health field for over 30 years. He has worked with diverse populations in various private and public sectors.

View all posts